Eye For Film >> Movies >> Strange Harvest: Occult Murder In The Inland Empire (2024) Film Review

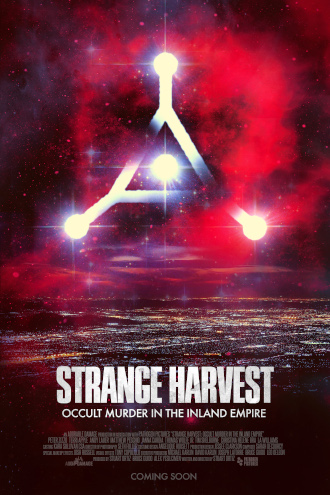

Strange Harvest: Occult Murder In The Inland Empire

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

There’s something about watching freeways from above that perfectly captures the loneliness, the anonymity of US life. In this vast country, people come and go with little discernable purpose. Sometimes they just disappear, and no-one ever notices. Sometimes they slide between jurisdictions and trails go cold. hearing the names Riverside and San Bernardino, true crime afficionados might think of the Zodiac or any number of the Golden State’s other legendary serial killers, some never caught, some with motives which remain obscure. Some things never make sense, so one might watch and watch, waiting for a pattern to emerge, and it’s like trying to find a meaningful sequence in the colours of the cars, in their blinking lights – one might be trying to connect with a fundamentally alien perspective.

This particular story is introduced by Detective Joe Kirby (Peter Zizzo), who, we are told, supervised the case between 2007 and 2015. He remembers responding to a call at the Sheridan family residence on Alton Avenue in the Shining Hills gated community, on 9 July 2010. We see what appears to be police footage of the approach to the house, of what was found there, but it’s not the fate of the family that disturbed Kirby so much as the symbol on the ceiling. “I looked at my partner and I said ‘Oh my God, he’s back.’”

Entering the story in the middle, we are introduced first to earlier events and then to subsequent ones, with director Stuart Ortiz perfectly capturing the style of the genre. Kirby is excellent, personable but keeping it low key so that he continues to feel like a real person, not a fictional character. In this he is ably matched by Terri Apple as homicide detective Alexis ‘Lexi’ Taylor, and the tone is maintained by a number of supporting players. The quiet, steady pace of the thing allows the monstrosity of the events discussed (and sometimes witnessed, by way of video and crime scene photos) to take on a still more dramatic aspect by contrast.

This format also grounds and restrains the film, so that the hints of cosmic horror which begin to emerge remain tantalisingly on the margins. Ortiz, like many a filmmaker before him, acknowledges a debt to HP Lovecraft, but his work here is more in tune with that author’s style than most, in that it resists the temptation to reveal too much or to offer reasoned explanations. Fans of cosmic horror literature will find numerous unsettling references buried in the details, also drawing on the work of Robert Bloch, but they won’t stand out to the uninitiated and the story never swerves to fit them in. They’re not just there to enable an Easter egg hunt; they allow Ortiz to examine the documented phenomenon of serial killers doing what they do for a perceived higher purpose, and the strangeness with which such behaviour can manifest to those who don’t share their beliefs.

Ortiz is also careful with what he shows us of the killer’s work. There are a couple of extremely gory scenes, but the camera is distant, observing without any sense of gratuitous indulgence. He does a lot more with suggestion, using crime scene photos of bloody walls or weapons and then letting viewers’ imagination fill in the details as the detectives discuss the context. We see photos of victims when they were alive and hear from the people who loved them, and the effect is far more potent than just another onscreen death which, let’s face it, ever viewer of genre films has long since become inured to. The mundane settings contribute further to the horror by reminding us that such killers can turn up anywhere, at any time.

Time is nevertheless important. Eagle-eyed viewers will begin to wonder about this right from the film’s opening montage, with its suggestion of secrets buried in deep time, exposed by way of an object in an evidence room which nobody in the investigatory team really knows how to interpret. Later suggestions of Mesopotamian short cuts made in error. Time running forwards, too, as it emerges that the killer was on a schedule; and cyclical time, leaving us with a warning, though not – as a post-credits sequence suggests – one that will be heeded. Time in the structure of the film itself, which will bring us back to the freeways, the figure of eight intersection which could be interpreted differently. How many times will you find yourself watching it? And what else might be watching?

Reviewed on: 25 Sep 2024